SWHHS rep says Lyon County is lacking both when it comes to welcoming refugees

By Per Peterson

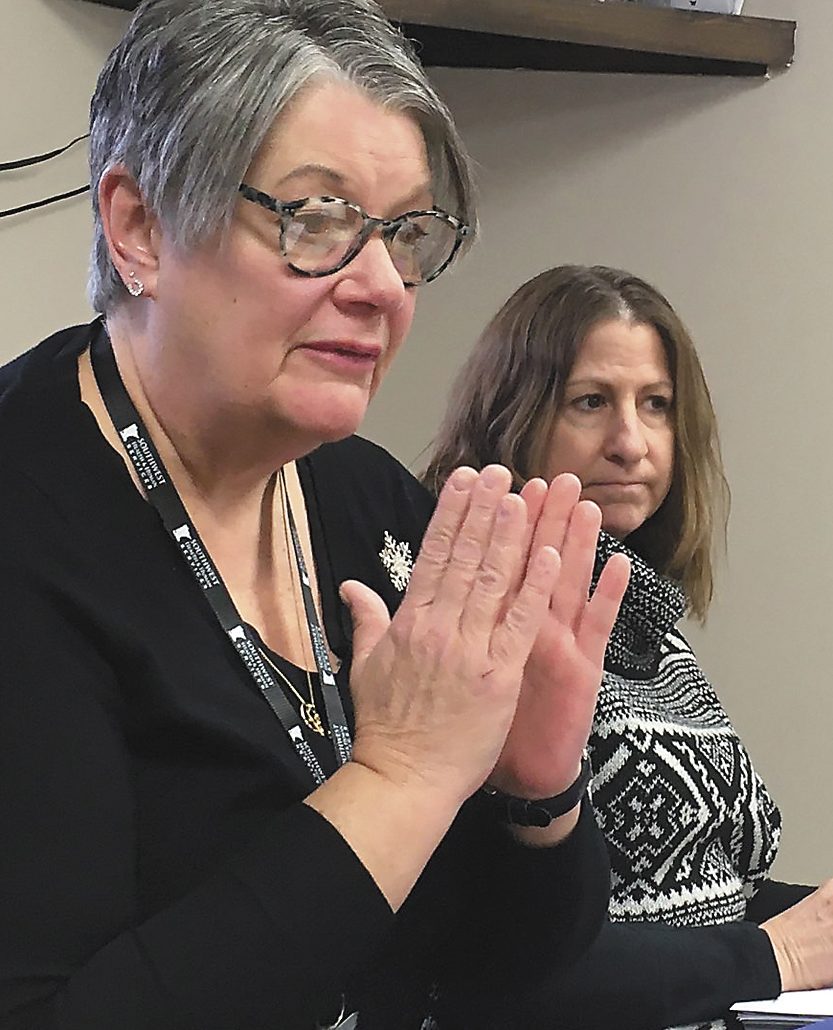

Beth Wilms could talk for hours about the refugee situation in the county and in Minnesota. The more she talks, the more passionate she gets, and the more frustrated she becomes.

Wilms, director for Southwest Health & Human Services, is fully ingrained in the refugee issue, which was featured under the public spotlight at last week’s Lyon County Board meeting. The board ultimately decided to hold a public hearing on what has come to be known as the “Refugee Resettlement Program” at 6:30 p.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 28, to shine even more light on a subject that has developed two sides. And Wilms wasn’t exactly content about what transpired at the meeting.

“I was defeated,” she said. “I think we have an opportunity to educate and provide information to our communities about what refugees are, what are immigrants … and then there’s that whole issue about undocumented folks who are coming into the communities.”

President Donald Trump has issued an executive order that will require state and local governments to provide written consent to the federal government before refugees can be resettled in their jurisdictions. This will take effect June 1 of this year and will apply to all arriving refugees, including those with family members who already live in Minnesota.

As for Wilms, she walked away from last week’s well-attended county board meeting with the feeling that there is more apathy than empathy in the community when it comes to welcoming refugees looking to make a home here. In her mind, opening arms to refugees is a non-issue, something that counties should be doing anyway — Nobles, Murray and Pipestone counties have already given consent for resettlement — so experiencing some contentiousness at the meeting came as a surprise to her.

“It’s a lack of information,” she said. “So we have to come up with a way of getting information out there. We’re going to strategize and figure out what we can do and how do we get that information out there. It’s not just in Marshall — it has to be in our local communities — Tyler, Tracy, Balaton.”

Consent to resettlement applies only to initial placement; refugees are free to travel and relocate to any community of their choosing after that.

Wilms has a difficult time putting a finger on why southwest Minnesota might not be as welcoming to refugees as she hoped it would be, or as it used to, and wonders if it’s generational.

“It’s become the perfect storm,” she said.

Wilms wants people to know that refugees — people who are in the process of seeking political asylum are fleeing their county to escape a war-torn society — are thoroughly vetted. Refugees, who Wilms said don’t have the option of going back to their native country, go through 20 assessments in their home country before being vetted by eight federal departments, including Homeland Security, here in the U.S.

“These are people who are leaving their homeland, they’re leaving their families,” she said. “It’s husbands leaving their wives, fathers leaving their children, hoping they can resettle.”

And, Wilms added, 100% of refugees are working within 60 days of arriving here.

“We have 2,700 open jobs in this area, and we should be welcoming people who want to come and work, because generally those are jobs that people here don’t want to take,” she said. “Refugees have the right to live anywhere. They have the right to move here after they resettle.”